The Slow Memory of Rome and the Labyrinth of Knowledge

This is a part of my fellowship journey at the Institute for the European Intellectual Lexicon and History of Ideas (ILIESI) at the National Research Council of Italy (CNR)

To whom it may concern:

The writer, Sajad Sepehri, is an Educational Development & Innovation Strategist at ISSH and a fellow researcher at the VU Amsterdam. An interdisciplinary researcher, he works on system design, EdTech, AI in education and research, knowledge management, and publication infrastructures.

He was awarded a fellowship at the Istituto per il Lessico Intellettuale Europeo e Storia delle Idee in Rome, for expanding his work on polymathic-generalistic epistemology as a methodological approach for developing Language-Agnostic Knowledge—an attempt to respond to the necessity of an epistemic shift in Open Science and beyond.

First Breath in Rome

The moment I stepped out of the terminal in Rome, the warm air hit me. It was not a comforting warmth; it was a trigger, a sensory key unlocking a traumatic memory of the homeland I have been away from for a lifetime. My host, Giuseppe, led us to the so-called limousine parking area—a name that lingered from another era, now populated by ordinary sedans. Our driver, a man with a mature face and the recklessness of a teenager, sped toward the city at 120 kilometers an hour, tailgating cars until they surrendered. Through the window I saw ancient walls scarred with graffiti, swarms of young people drawn to the night like moths to a flame.

This fellowship was meant to be an intellectual pilgrimage. Yet in those first hours I was consumed by homesickness. A part of me remained in Tirana, a part with my family in the Netherlands, and another part—aching and persistent—in Shiraz, the city I have been away from for many years. The next morning, I made a video call to my wife, Nina, to share our ritual of morning coffee. We talked about our son, who hates school just as his father once did. Later, I went searching for a supermarket to buy eggs, oil, and bread—a small act of replication, a way of anchoring myself in a world that felt adrift.

Rome introduced itself as a city with a “slow memory.” Unlike the crisp orderliness of the Netherlands, life here feels layered and deep. History is not locked away in museums; it is sedimented into the very stones, memories recorded slowly on the body of the city itself. This first week was less about libraries or archives than about encounters—conversations that shifted my project more than any manuscript could.

A Confession

I am not a place person, I am a people person. Monuments, ruins, or landscapes do not move me if I stand before them alone. What animates a city for me are its conversations, its dinners, its encounters. That is why in my first week I was eager to meet, to talk, to write—not to wander through the sights. Rome, for me, was never going to be the Colosseum; it was always going to be Cristina, Lorenzo, Federico, Lisa, Ramazan, Ali, Francesca, Lottie, Pamela, Fillipo, and the other faces with whom we had non-verbal communications.

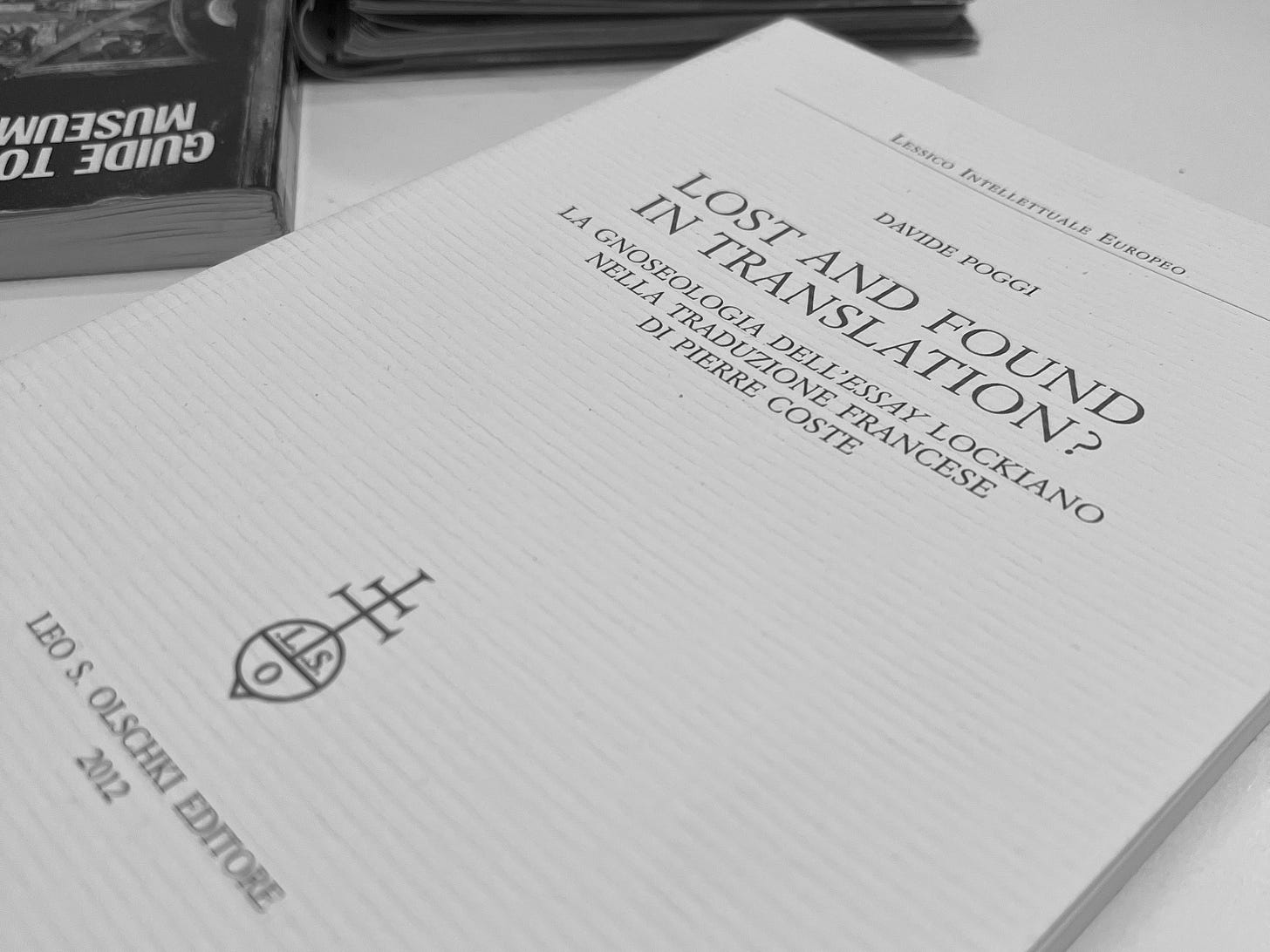

One can distinguish between those who form attachments to landscapes and those whose sense of belonging is mediated through relationships. My orientation is the latter. Perhaps it is because of my status as an atopos1—placeless, alien, exiled. Belonging, for me, has always been compensated through people, never through soil or stone. That is why I feel Albanian, I feel Iranian, I feel Kurd, I feel even Italian—and no one has the authority to police that feeling.

From the political view Agamben in his Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare life explained it. Exile and statelessness cast me as homo sacer, life reduced to its minimum, unprotected, unrecognized. But that very exclusion created the strangeness of atopos: the vantage point of never fitting, of seeing connections others overlook. This is what I call “Life On the Edges”. What is political deprivation in one register, becomes philosophical fecundity2 in another. My belonging has never been secured by soil or passport; it has been remade through people, through encounters, through relation itself.

This does not mean I am numb to places. I am filled with amazement, awe, thought, and joy by history, by heritage, by stones, by bridges. But for me these feelings are never solitary—they are always tethered to relation. To stand before a monument with Nina is not the same as standing there alone; her presence transforms stone into memory. To sit at a historical piazza with a cup of the best coffee of my life3 is not just scenery, it is a relationship—with the act of writing, with thought itself. When I write, I am in my own company. Again, there is a relationship. As Edward Casey writes in Getting Back into Place, place is experienced through memory, body, and relation. I could not agree more. Rome is doing exactly that to me—through the incredible people I meet, the foods I eat, and the words I read or write while looking at its historical stones. I am becoming Italian4.

1. I Found a Treasure, and It Was a Person

My first full day was spent at the Istituto per il Lessico Intellettuale Europeo e Storia delle Idee (ILIESI). There I met Cristina Marras, the institute’s Research Director. From the first words we exchanged, I felt an exhilarating sense of recognition. We stood on different banks of the same river, yet somehow spoke the same language.

For years, I had been developing ideas about knowledge systems, intuitive and feasible, but lacking formal grounding. Cristina introduced me to her work on pragmatic modeling and the constitutive role of metaphors in organizing knowledge. I’ll write a review of her book soon. It was as if she had handed me the precise epistemological framework I had been tentatively reaching toward in the shadow.

I left the institute convinced I had found a treasure—a treasure named Cristina Marras.

That evening, in autumn rain, we picked up an authentic Italian pizza. It was so profoundly different from every counterfeit “Italian pizza” I had ever tasted that it felt like another philosophical revelation: even pizza can reveal the gap between imitation and reality. Coffee has a similar situation. However, I must admit that I am incredibly proud of the Albanian coffee.

2. A Language’s “Flaw” Can Be Its Greatest Strength

On my second day I met Lorenzo Giovannetti, a philosopher whose work on Plato has earned recognition from the International Plato Society. He teaches at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” and his path winds through Rome, Oxford, Tübingen, Sussex, and beyond—a life steeped in Greek thought and its afterlives.

We spoke of the Persian pronoun او (oo). From a computational standpoint, it is “flawed”: it carries no gender and can mean either “he” or “she.” In Cristina’s perspective, it is inadequate, and this inadequacy presents an opportunity for meaning-making. Lorenzo and I agreed, what one framework sees as a bug, another recognizes as richness. Persian poetry thrives on this ambiguity, suspending gender and letting love exist beyond categories. For centuries, this single pronoun has kept alive questions no grammar book could resolve.

This insight reinforced what I have argued: a multilingual knowledge system cannot be reductionist. It must embrace ambiguities, not attempt to sterilize them. It seems that the current Euro-centric notion of multilingualism is disastrously reductionistic.

3. The Most Creative Space Is the One Between Categories

Lorenzo brought another connection. He reminded me of the Greek word atopos—literally “without a place.” He said that Socrates was called atopos, which means absurd, uncategorizable, and placeless.

Pierre Hadot used the concept to highlight Socrates’ unique character as a philosopher who couldn’t quite be “placed” within the social or intellectual conventions of his time

My legal status is “alien.” I was stateless, suspended between nations. My academic work resists belonging to any single discipline. My life unfolds between languages. For many this in-betweenness feels like exile. But I recognize it as a vantage point.

I call it a Polymathic-Generalistic epistemology: the ability to see connections invisible to those rooted firmly inside categories. True creation happens not in the center but on the edges, in those porous spaces where worlds brush against each other. Therefore, the PGE is a methodological approach.

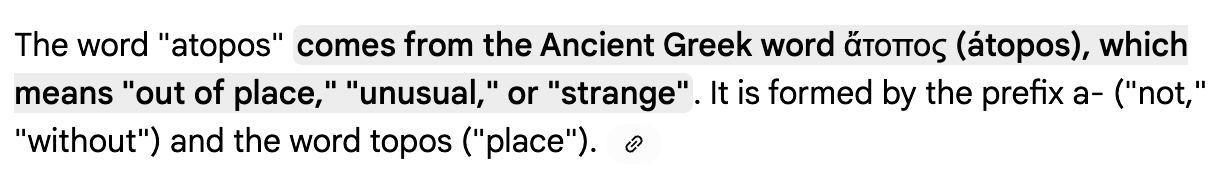

4. Words Are Travelers, and They Collect Souvenirs

One evening, over dinner with Cristina Marras, Ramazan Turgut, Federico Silvestri, and Lisa Reggiani, we ate pizza and supplì and joked about words. (It is impossible to be with Cristina and not talk about words.)

Federico, a brilliant researcher of contemporary philosophy, spoke of Italy, its north-south divides, its economic struggles, its literature. Lisa, a technologist at ILIESI, thoughtful, calm, mostly listening and humble. It was one of those dinners where conversation moves lightly from etymology to politics to jokes, the kind of evening that convinces you philosophy is not confined to conferences and lexicon archives, but thrives in shared meals.

I brought up the word mohabbat (or muhabbet). Its root is Arabic ح ب ب, meaning love. From there it traveled:

Persian: an act done out of loving and caring.

Turkish/Ottoman: conversation, dialogue (a friendly one maybe)

How can one word hold absolute love, a loving act, and a chat over tea? Because words are travelers. They collect souvenirs from each culture they pass through, carrying their ghosts into the present.

This is why translation alone is never enough. A robust knowledge system must honor the sediment of meanings without flattening them. What I have been calling a “semi-structured” approach is, I now realize, aligned with Cristina’s middle-out approach—a way to preserve nuance without dissolving into chaos.

In the Language Agnostic Knowledge framework, I aim to expand and conceptualize knowledge through co-creation. Translation, contrary to its current perception as a secondary or derivative act, is not considered such in this framework. It is a form of pragmatic modelling in which a Piece is re-inscribed in a new linguistic and cultural context. This act has a dual role: one part of the original knowledge is necessarily lost, yet at the same time new context and new knowledge are created. Translation is thus an extension of the original, not its dilution. Its attachment and closeness to the original are essential, for it depends upon it; yet it simultaneously expands the epistemic field by producing new meaning. LAK therefore rejects the treatment of translation as second-hand work and affirms its value as co-equal knowledge production.

5. To Build the Future of Knowledge, We Must Talk to the Ancient Greeks

My conversation with Lorenzo circled back to philosophy’s foundations. He described an ancient model of language:

Plato’s Window in his theory of Forms: the mind, through dialectic, can apprehend reality itself. Language participates, but imperfectly—it points toward truth but can also mislead.

I, on the other hand, was referring to the mirror metaphor, which Leibniz (a Post-Cartesian philosopher) frequently used in his work, as Cristina rightly identifies as among the most recurring metaphors.

Mirror: Leibniz often speaks of language as a system of signs or symbols (characteristica universalis). Words reflect concepts, which in turn reflect reality. But the reflection is indirect—signs represent ideas, which represent things.

Which metaphor we choose is not trivial. It sets the epistemic architecture for what knowledge can be.

The Labyrinth Ahead

By the end of the week, I felt I was not standing at the start of a straight road but in the mouth of a labyrinth. Every turn promised discovery, every corner a dead end or a new connection.

In a workshop earlier in the week, I had already met Francesca, Lottie, Pamela, and others, each encounter adding another thread to the web. And today, Fillipo Mosca, a philosopher, presented a chatbot project on Wittgenstein’s Oracle. I guess that this project is related to a previous project here. He was so generous to spend time explaining his work, which made me rethink the scale of what is possible with AI. I realized that this possibility is very much dependent on how well a CS graduate can grasp philosophical and epistemic abstraction.

Yet one thought lingered:

universities, with their glacial pace, will never catch up with the storm of AI and the speed of corporate labs. Unless they begin working with small, emerging technology groups—those rare companies that still earn trust through creativity rather than marketing—academic R&D risks becoming an expensive exercise in futility.

The irony of Rome is that in a city of ruins, one feels the pulse of life more vividly than in the sterile offices of “innovation.”

Something important is unfolding here. Perhaps it is only the slow memory of the city teaching me to walk differently. Perhaps it is the conversations, the words, the shared meals. Or perhaps it is the recognition that knowledge itself is a labyrinth (or an ocean!)—and I am already inside.

What happens when the pressing questions of humanities in the digital and AI era collide with the slow memory of an ancient city?

Italians might say, “Don’t worry! Relax!”

Keep reading! Lorenzo, the philosopher, will clarify. I learned about the term from him.

the ability to produce many new ideas

with all due respect to the Albanian coffee, which is an interpretive mapping of the Italian

Whenever an elderly woman on the street approaches me and asks me a question as if I were an Italian, I feel a surge of joy. I politely inform them (in English) that I am honored that they mistook me for an Italian, but I am actually a non-Italian Italian!