Asymmetrical Forest: My Reflection on the Visual Metaphors of Open Science

This is a part of my fellowship at the Institute for the European Intellectual Lexicon and History of Ideas (ILIESI) at the National Research Council of Italy (CNR)

1. Introduction: A Workshop in “Doing Open Science”

Recently, I had the distinct privilege of participating in a workshop at the historic Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) in Rome. This was not a typical academic seminar. Its objective, guided by the thoughtful work of our hosts, was to practice the very principles of Open Science in the process of creating a book about it. The gathering was a living experiment in collaborative knowledge creation, aiming to embody its subject matter. The central figure of our discussion was Francesca Di Donato, a researcher at CNR-ILC, who presented a chapter from her work-in-progress on the visual metaphors that have shaped the Open Science movement. This article is a personal reflection on her incisive presentation and the rich, stimulating discussions that followed. The opportunity for my colleague, Ramazan, and me to join this brilliant group was made possible through a research fellowship and the generous support of Cristina Marras1, whose dedication to the project was tangible. As the workshop unfolded mainly in Italian, it added a rewarding layer of cross-cultural engagement to this intellectual experience. The purpose of this article is to trace the evolution of Open Science metaphors as charted by Di Donato and to offer a critical yet pragmatic extension of her final, powerful proposal: the metaphor of the forest.

2. The Metaphorical Ladder: Charting the Visual Language of Open Science

Context and Attribution

Understanding the visual metaphors used to describe Open Science is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for grasping the movement’s evolving values, priorities, and cultural assumptions. These images are not just decorative—they shape definitions and reveal the underlying research cultures that produce them. The following intellectual cartography, which traces a clear evolutionary path in the visual language of Open Science, is drawn directly from the meticulous research Francesca Di Donato presented for her forthcoming book. This section serves as a summary of her analysis.

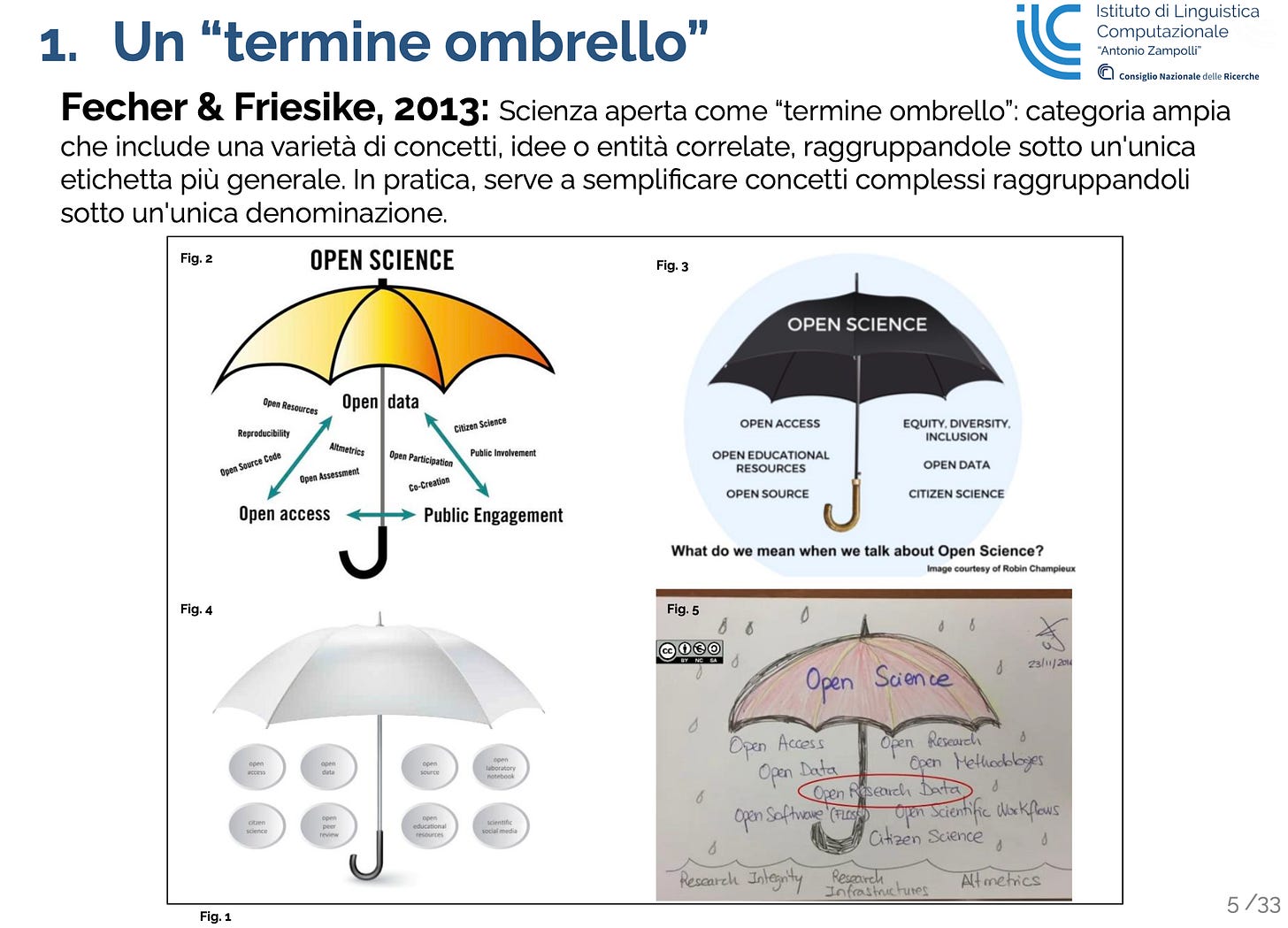

2.2 The Umbrella and the Mushroom

As Di Donato explained, the journey begins with the ‘umbrella’ metaphor, famously introduced by Fecher & Friesike (2013). The umbrella is a man-made artifact, a tool created to serve a specific purpose: to collect and shelter a variety of related concepts under a single, simplifying term. It is an image of utility and consolidation. Yet, as Di Donato demonstrated through examples from communities like Public & Science Sweden, the EOSC-hub project, and Brazil’s FIOCRUZ, what lies under the umbrella varies significantly. Each interpretation reflects the priorities of its respective community, arranging practices like Open Access, Open Data, and Citizen Science in different configurations and hierarchies.

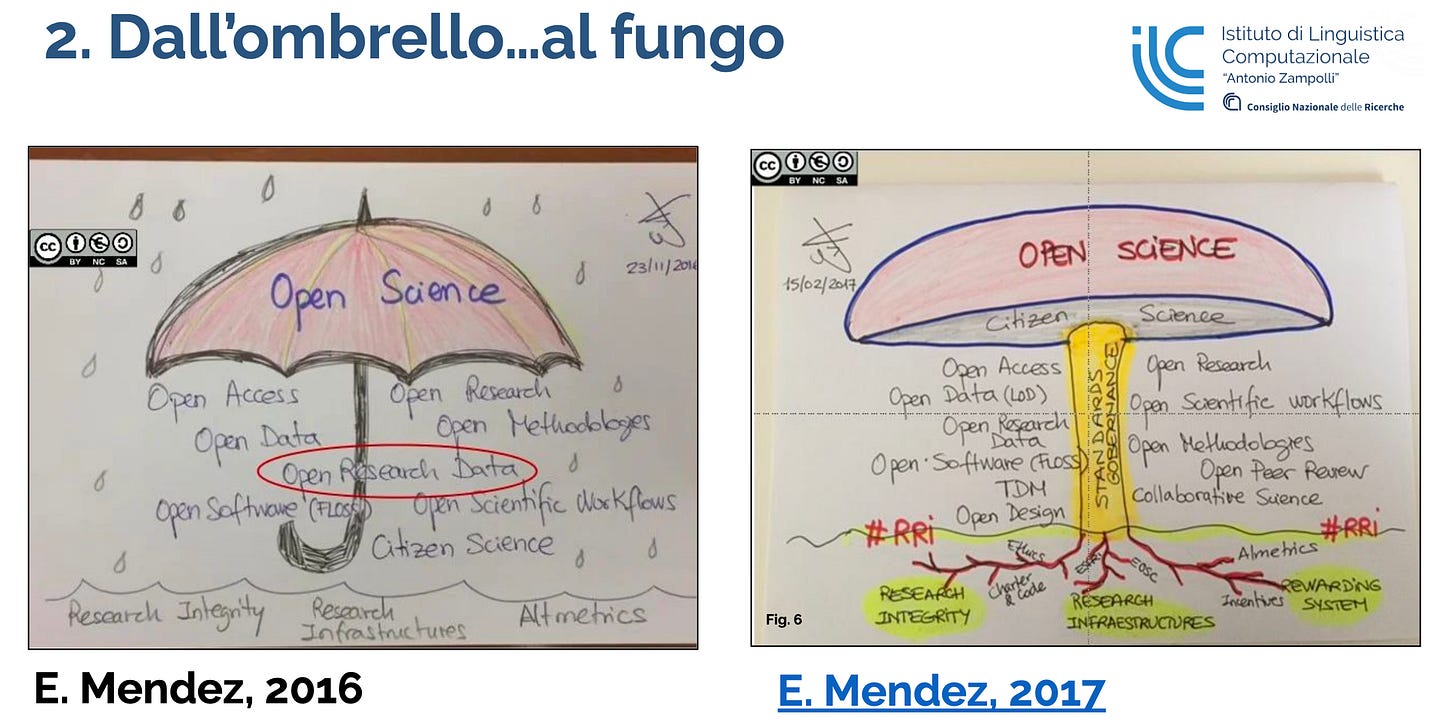

Di Donato then highlighted a significant conceptual shift with the introduction of the ‘mushroom’ metaphor by Eva Méndez. This marked a crucial move away from a man-made artifact toward a natural, living organism. The mushroom is not merely a container for visible practices. Its power lies in introducing the idea of a hidden, submerged system—a root network analogous to an iceberg’s submerged mass. Di Donato detailed its anatomy: the gills (lamelle) represent Citizen Science, and the stem (fusto) symbolizes standards and governance. Crucially, the roots represent the foundational elements of research integrity, infrastructure, and alternative evaluation systems, which are essential for nourishing the visible parts of the organism.

2.3 The Wheel and the Tree

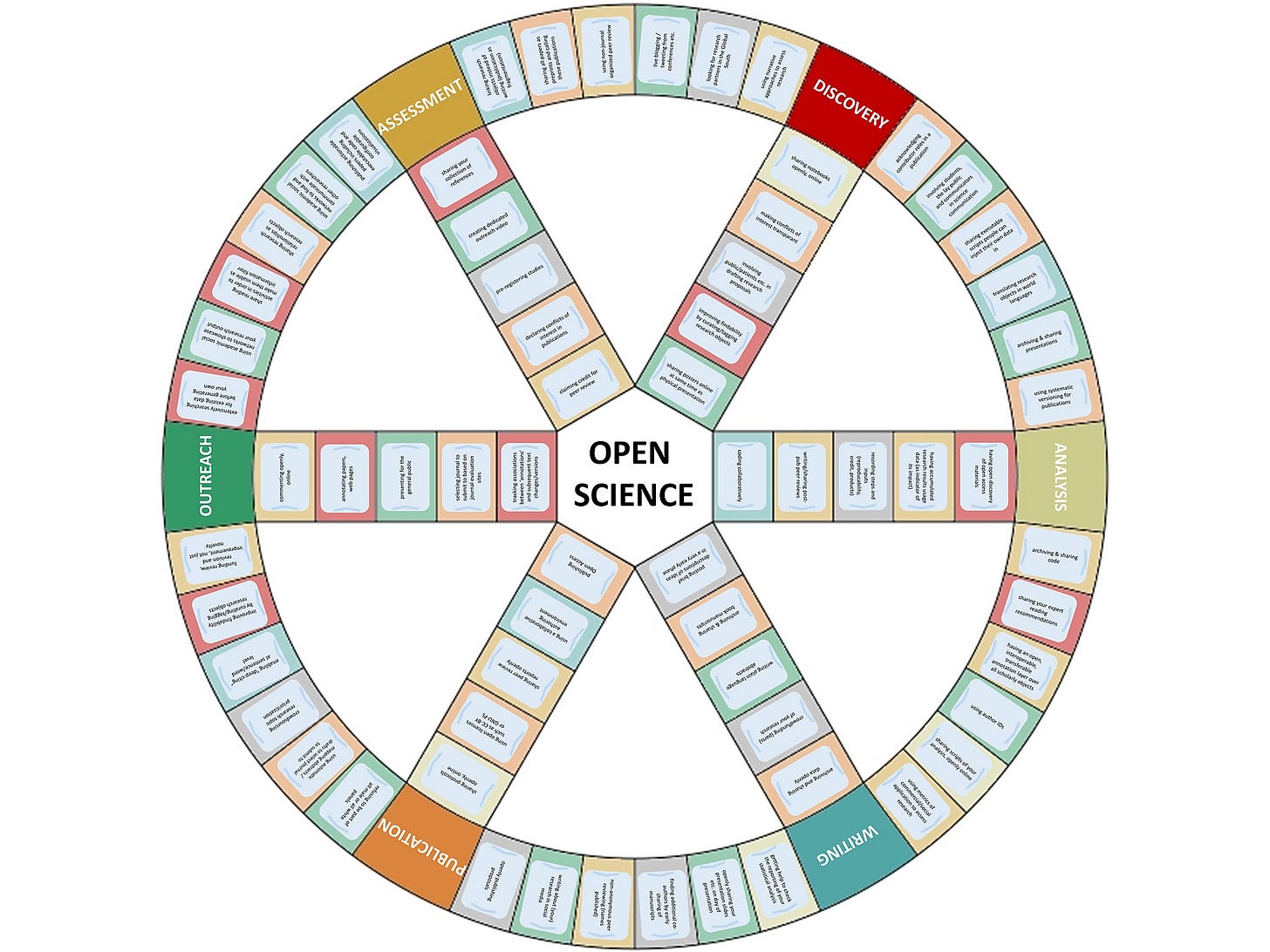

The next step in this metaphorical evolution, Di Donato showed, is the ‘wheel’, developed by Kramer & Bosman (2017). Shifting back to a human invention, the wheel represents Open Science as an infinite, circular research workflow. It maps practices onto different phases of research—from discovery and analysis to publication and outreach—in a continuous loop. As one of humanity’s most important inventions, the wheel metaphor elevates Open Science from a mere collection of practices to a fundamental process, a new engine for knowledge production. Di Donato noted that the wheel also evokes the hermeneutic circle—the interpretive process where understanding a text, or in this case, a research field, requires a continuous movement between the whole and its constituent parts.

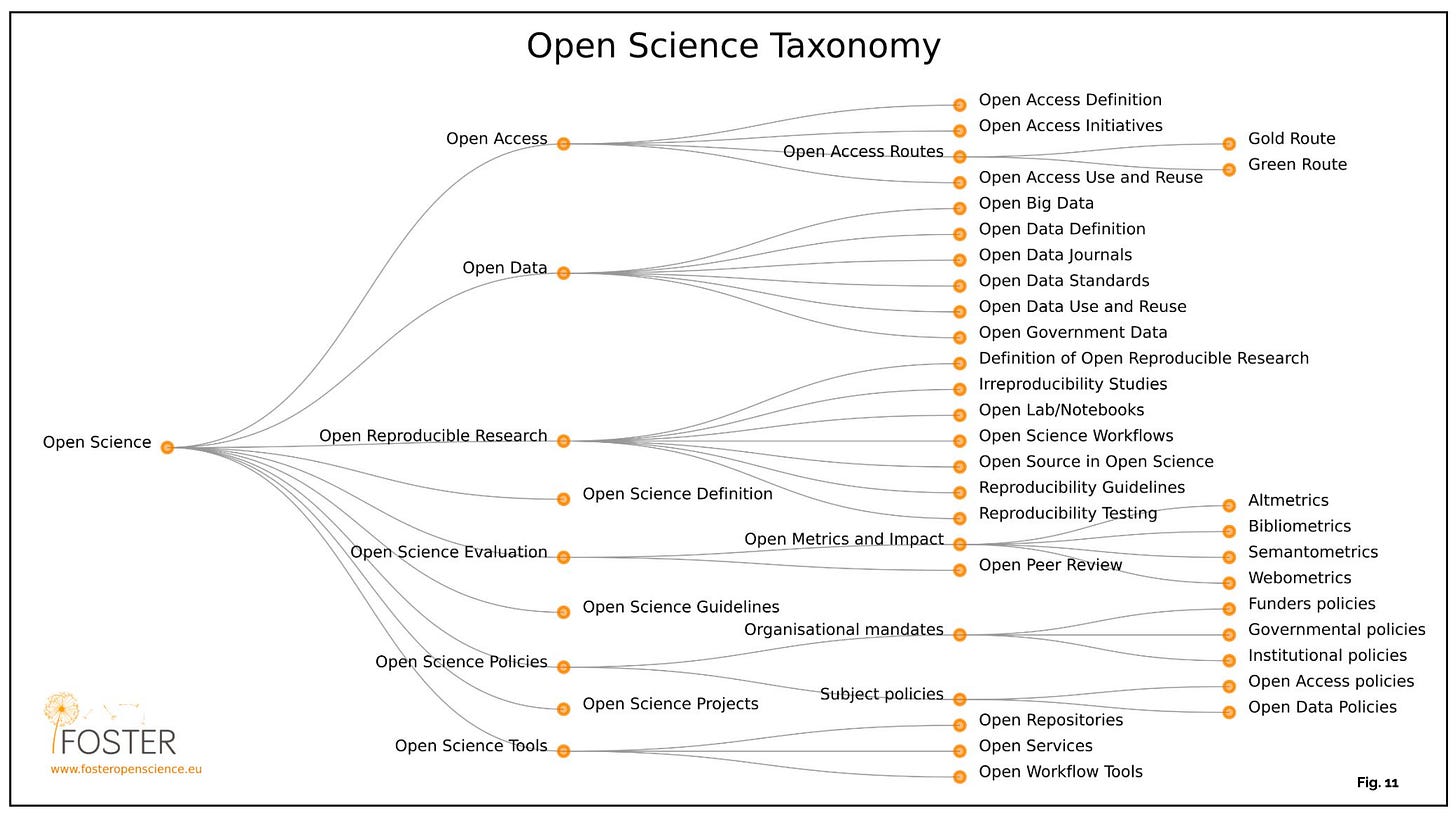

This idea of process is further systematized in the ‘taxonomy’ and ‘tree’ metaphors, exemplified by the FOSTER taxonomy. The tree organizes the components of Open Science into a hierarchical structure, bringing order and detail to the ecosystem. However, the tree is laden with deeper historical symbolism. Di Donato powerfully recounted how trees became emblems of resistance and revolution. In the American Revolution, the “Liberty Tree,” an elm in Boston, became a rallying point for resistance. During the French Revolution, a priest named Norbert Pressac replanted an oak as a patriotic symbol, an idea that spread rapidly. Quoting Stefano Mancuso, Di Donato explained the profound symbolism: “Dying or dead nature must be only the emblem of despotism. Conversely, living and productive nature... must be the image of liberty.” This association imbues the Open Science movement with a legacy of radical, systemic change.

2.4 The Graph

The final precursor to the forest is the ‘graph’ metaphor, notably used in a UNESCO (2020) document. A graph is a mathematical structure composed of vertices and arches, a model that immediately evokes the interconnected topologies of the internet and the World Wide Web. As presented by Di Donato, this metaphor powerfully emphasizes three core UNESCO objectives: making knowledge openly available, enhancing collaboration and information sharing, and opening the scientific process itself to actors beyond the traditional scientific community. The graph portrays Open Science not as a static collection or a linear process, but as a dynamic, decentralized network of relationships. This vision of a complex, living network serves as the perfect bridge to Di Donato’s own proposal: the forest.

3. The Forest of Open Science: A New Ecosystemic Vision

Context and Proposal

Francesca Di Donato’s proposed ‘forest’ metaphor is more than just the next step in this progression; it is a sophisticated synthesis that absorbs the strengths of its predecessors. It offers a richer, more dynamic, and more value-laden vision for Open Science, framing it as a living, collaborative, and intelligent ecosystem.

An Inclusive and Collaborative Ecosystem

In Di Donato’s interpretation, the forest seamlessly integrates the most potent elements of previous metaphors. It is a natural organism like the mushroom, its revolutionary roots recall the symbolism of the tree, and its vast, interconnected root system functions as a living graph. She attributes to this forest a series of profoundly positive qualities that align with the highest aspirations of the Open Science movement:

• Collaboration: The forest ecosystem is built on a model of mutual support, as theorized by Kropotkin (1902). Trees are not isolated competitors but members of a vast community connected by a subterranean network that exchanges nutrients, water, and information.

• Inclusivity and Biodiversity: The forest is a collective enterprise where diverse actors contribute to the health of the whole. In this ecosystem, even “dead trees”—completed projects or retired datasets—continue to provide nourishment and structure, fulfilling a vital function.

• Collective Intelligence: Drawing on contemporary plant science, Di Donato describes the forest as a “swarm of swarms.” Individual plants possess a distributed, modular intelligence, and the forest as a whole forms a collective intelligence far greater than the sum of its parts as Ramazan commented in the discussion.

• A Shift in Values: This ecological vision fundamentally changes how we assess value. Citing Mounier (2022), Di Donato argued that the forest metaphor encourages us to move beyond conventional metrics of efficiency and excellence and ask new, more profound questions about our work: “Is it sustainable? Is it inclusive? Is it creative? Is it alive?”

My Reflections

This compelling and beautiful portrayal of the Open Science forest sets a high ideal. However, it is precisely its power that necessitates a critical re-evaluation.

4. A Critical Re-reading: The Inherent Asymmetries of the Forest

Context and Critique

Any potent metaphor risks becoming a romanticized ideal if not grounded in the complexities of reality. During the workshop, I felt compelled to offer a critical perspective, arguing that the true strength of the forest metaphor lies not in its idealism but in its capacity to represent the very real tensions and inequalities that persist within our knowledge ecosystems. A factual examination of a forest reveals it to be a site of structural asymmetry, not purely egalitarian harmony.

Beyond Romanticism: Confronting the “Dark” Forest

To truly serve as a pragmatic tool (I’ve learned a lot during my skimming through the work of Cristina Marras on pragmatic modelling and middle-out approach and the constitutive nature of metaphor), the metaphor must encompass the “darker” aspects of the forest—the realities of competition, exclusion, and inequality. These natural processes offer powerful parallels to the systemic challenges facing the Open Science movement:

• Unequal Resource Distribution: In a real forest, tall canopy trees monopolize sunlight, often starving the understory plants below. Root systems compete fiercely for water and nutrients. This directly mirrors how privileged institutions and Anglophone-centric research dominate the global knowledge landscape, capturing the majority of visibility, funding, and resources.

• Absence of Equal Opportunity: A seed’s survival is heavily dependent on the chance of where it lands. A spot with fertile soil and adequate light allows it to thrive, while an equally viable seed may perish in deep shade. This reflects the systemic barriers and positional advantages in academia, where success is often contingent on pedigree and geography rather than merit alone.

• Exclusion and Competition: Some plant species engage in allelopathy, releasing chemicals to actively suppress the growth of competitors. This is a stark metaphor for the persistent competition for funding and recognition, the gatekeeping practices of established journals, and the institutional rivalries that can stifle collaboration.

• Efficiency Without Fairness: A forest is a remarkably resilient and efficient system, but its efficiency is achieved through brutal cycles of dominance, decay, and regrowth. It is a system of winners and losers. This parallels how the current scientific ecosystem can be highly efficient at producing a massive volume of outputs while failing to be fair or equitable in its methods of evaluation and reward.

Mapping the Gaps in Practice

This critical lens helps synthesize a core problem: the Open Science movement, in its current form, resolves access asymmetry far more effectively than it resolves evaluative asymmetry. We have made great strides in lowering the barriers to reading scientific literature, but the deep-seated asymmetries of recognition, reward, and linguistic privilege persist. The infrastructures, metrics, and incentive structures remain predominantly Anglophone and tilted toward quantitative measures that favor already-dominant institutions. The forest metaphor’s greatest value, therefore, is not in romanticizing openness but in its capacity to make these tensions visible, challenging the status quo and forcing us to confront the gaps between our principles and our practices.

5. Enriching the Metaphor: Towards a Pragmatic and Constitutive Image

Context and Synthesis

For a metaphor to be truly useful, it must move beyond mere description. It must be complex enough to represent reality and robust enough to guide action—to become a constitutive tool for building a better system. The collaborative discussions at the workshop became an exercise in enriching the forest metaphor, layering it with the nuance needed to make it both a map of the present and a guide for the future.

Insights from a Community of Practice

Our breakout groups—a mix of librarians, philosophers, and other researchers—began to annotate Di Donato’s image, adding elements to represent both principles and problems. Our group, among others, proposed several critical additions:

• A frame or boundary around the forest, representing the protecting principles, ethical guidelines, and shared values (like multilingualism and pluralism) that must define and defend the ecosystem.

• Facilitators and unifiers in the sky above—forces of connection and aggregation like bees, wind, and birds, and perhaps even AI represented as an airplane—that pollinate ideas and bridge communities as a sign of openness of the forest to naturalize and integrate artificial intelligences.

• A crack or canyon cleaving the ground, symbolizing the digital divides, resource gaps, and systemic fragmentations that prevent the root network from being truly universal.

In a particularly insightful contribution, my colleague Ramazan invoked the poet Nazim Hikmat2, suggesting that if the individual trees are researchers and institutions, then the “invisible labor” of maintenance, care, and community-building is the glue that binds them into a forest, making the whole greater than the sum of its parts. Cristina Marras elegantly reframed this concept as the unseen “photosynthesis”—the quiet, essential labor that converts light into energy and nourishes the entire system.

An Argument for Nuance

During our discussion, Francesca voiced a preference for keeping the core image simple. I respectfully disagree, arguing that a pragmatic and constitutive metaphor may require detail and nuance. The Mona Lisa, while a simple portrait of a person, contains infinite, vital details. Similarly, a complex image allows us to identify specific challenges and opportunities. By explicitly visualizing the frame that protects, the canyons that divide, and the pollinators that connect, the metaphor becomes a practical tool. It transforms from an image that simply describes an ideal into one that helps us constitute a more equitable practice by making its gaps, asymmetries, and essential components visible and actionable.

Every metaphor must function as an orienting device. It should momentarily capture the thinker, establish a frame, and provide the scaffolding through which knowledge can be organized. Cristina Marras and others name this the pragmatic operators: the capacity of a metaphor to guide the act of structuring thought. With the forest, one does not need to over-explain in order to achieve initial recognition. The concept is immediately available to human cognition; class and category emerge almost intuitively. What follows are the particularities, the differentiations, the multiple layers of meaning. My argument is that producing a spectrum of images—a simple outline, a moderately detailed sketch, and a fully articulated rendering—introduces variability and negotiability. It acknowledges the multiplicity of perspectives, even the darker, more pessimistic readings of the status quo. This adaptability transforms the forest into an inclusive framework, capable of serving not only as an emblem of idealized openness but also as a pragmatic diagnostic tool.

The framework then resists closure. It remains open, in the spirit of Open Science, to diverse pragmatic interpretations while preserving the integrity of the central metaphor: the forest as an ecosystem with distinctive properties. Within this orientation, detail is not a distraction but a means of enabling the metaphor to act as both descriptive and constitutive. Inspired by Marras’s reading of Leibniz, the forest may function as a mirror—reflecting configurations of knowledge—or as a maze—disclosing the complexities, barriers, and asymmetries embedded within it. This duality is precisely what makes the metaphor effective: it does not freeze meaning but sustains a dynamic play between recognition and exploration.

6. Conclusion: A Personal Reflection on Hope, Pessimism, and the Future

Recapitulation and Personal Duality

The central argument of this reflection is that the forest is a profound and powerful metaphor for Open Science, but only when we embrace its full, un-romanticized complexity. It must contain both the cooperative, life-giving ecosystem we aspire to and the “darker,” asymmetrical realities of competition and exclusion we currently inhabit. The experience of the workshop left me with a deep sense of this duality. On one hand, I was filled with admiration for the passionate, dedicated researchers I met. In an old building that reminded me of my old school, they pour their love into foundational fields like philosophy, linguistics, and epistemology. Between discussions, over the fast coffees that punctuated our breaks, I saw a community dedicated to work whose societal impact is not immediately marketable but is profoundly essential.

On the other hand, I carry a persistent pessimism about the broader injustices of the global knowledge economy, where vast sums are allocated to weapons while these same scholars struggle for funding, and where the academic reward system often feels disconnected from the pursuit of genuine understanding. This workshop crystallized that tension for me: the hope inspired by a small group of brilliant, caring individuals against the backdrop of a deeply flawed global system.

Gratitude and a Look Forward

I am immensely grateful to Francesca Di Donato for sharing her brilliant work and for her inspiring openness to dialogue and critique. My thanks also go to Cristina Marras, Ramazan, and all the participants whose insights enriched the day immeasurably. I eagerly await the publication of Francesca’s book and hope it finds the wide readership and spirited discussion it so clearly deserves.

Ultimately, this experience reinforced my belief that balancing pessimism with hope is not a contradiction but a necessity. Critical and collaborative reflections like the one we shared in Rome are essential for steering the Open Science movement away from romantic idealism and toward its substantive, transformative promise. Let us hope this vision for an open science, or دانش باز, continues to grow.

7. References

All references can be found in Francesca’s work:

Di Donato, Francesca. “Le immagini della scienza aperta”. Presented at the Che cos’è la scienza aperta? Le immagini della scienza aperta, CNR, Roma, September 19, 2025. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17158926.

Cristina Marras is a Research Director at ILIESI (Institute for the European Intellectual Lexicon and History of Ideas), part of the Italian National Research Council (CNR), Rome.

Her research focuses on Early Modern philosophy (especially Leibniz), theory of metaphor and pragmatics, digital humanities, and the intersection of language, imagery, and conceptual modelling in philosophy and science.

She earned her PhD in Philosophy (summa cum laude) with a thesis on the metaphorical network in Leibniz’s philosophy.

Nâzım Hikmet’s statement about living free like a tree is “To live! Like a tree alone and free, To live! Like a forest in brotherhood/sisterhood!“ in Turkish: Yasamak bir agaç gibi, tek ve hür, Ve bir orman gibi kardesesine